1:1 Redemptions for Some, Not All

Investigating how stablecoin redemptions rely on access, solvency, and timing

The Crucial Promise

Stablecoin issuers offer a simple proposition: send one dollar to the stablecoin issuer in exchange for a digital token that represents that dollar on a blockchain. That stablecoin, for example, can be used as a payment tool or a store of value, and the issuer promises to redeem it for a dollar later. This simple promise of 1:1 redemption, known as par-value exchange, is more complicated than many realize and depends on a series of assumptions.

Redemption Access: Most users cannot redeem stablecoins directly with issuers like Circle (USDC, Section 13, ‘Claim on Funds’) and Tether (USDT, Section 4.1, Issuances and Redemptions). Instead, users rely on intermediaries like open-market exchanges (e.g. Coinbase), where prices fluctuate with supply and demand. While issuers do offer 1:1 redemption to users who have verified financial accounts directly with the issuer, that access is tightly restricted. It typically requires submitting to full KYC/AML checks, meeting minimum redemption thresholds, agreeing to transaction fees, and operating within approved jurisdictions. For everyone else, access to redemptions, and therefore to the par-value exchange, is indirect.

This results in a two-tiered system: institutional clients (i.e., those who have accounts with stablecoin issuers) can redeem directly with stablecoin issuers while other users are left to trust that the peg will hold in public markets. Retail users have no contractual redemption right with the issuer, only indirect access to par value exchange via intermediaries. This system is particularly punishing during times of market stress. When the price in the secondary-market (where most users interact with stablecoins) falls below $1, as it did during the USDC-SVB crisis in 2023, the only way out for many users is to sell on these open market exchanges, sometimes at a significant loss.

Furthermore, to fulfill redemption requests, stablecoin issuers must meet two critical conditions: they need a balance sheet backed by high-quality, liquid assets, and they must maintain reliable access to the banking system.

Liquidity and Solvency of Issuer’s Reserves: Even for those with redemption rights, issuance-on-demand is not guaranteed. The 1:1 promise works when the stablecoin issuer has both solvency, having enough assets, and liquidity, the ability to convert its assets into fiat quickly and without loss.

Access to the Banking System: Stablecoin redemptions ultimately only happen when fiat is transferred back into a user’s bank account. If a stablecoin issuer loses access to its bank accounts, it will no longer be able to process redemptions. (Practically, the issuer would also likely be unable to issue new tokens.). Without banking access, the only remaining exchange channel is the peer-to-peer secondary markets, which cannot adjust the supply or demand to enforce the peg.

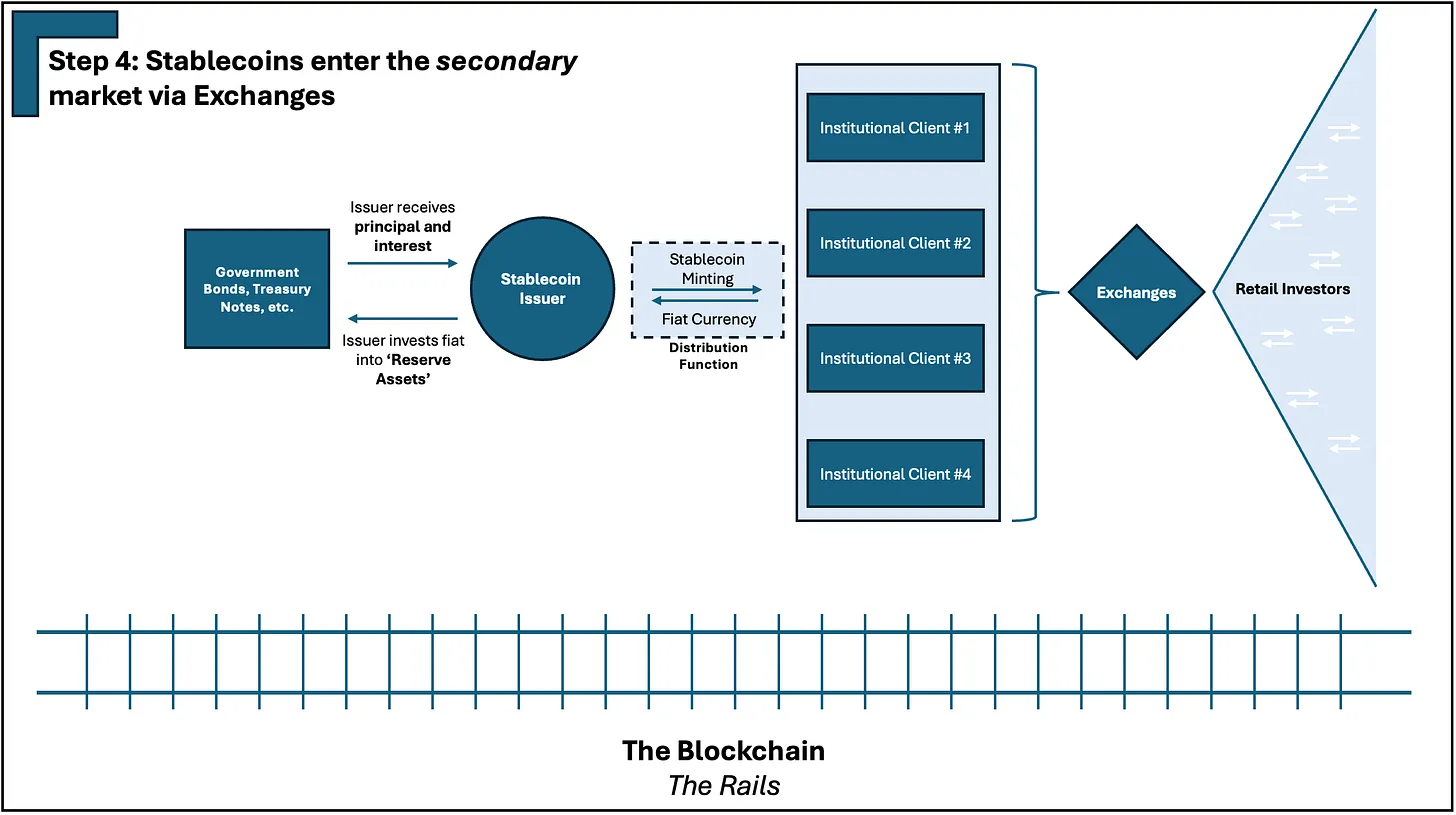

The Stablecoin System

To better understand the importance of par-value exchange, let’s walk through the various stakeholders of a stablecoin system:

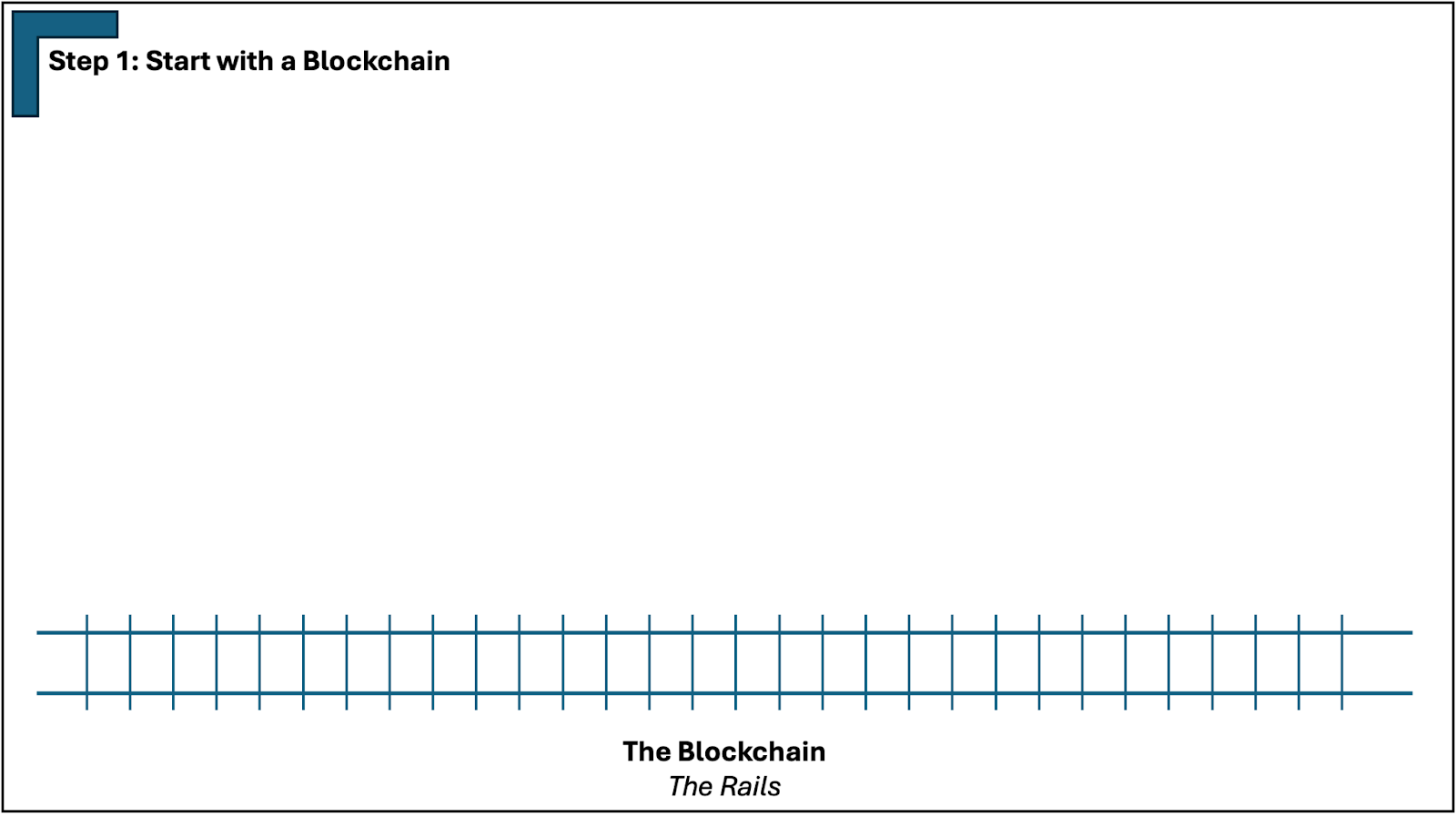

A blockchain is the technology layer that underpins stablecoins. There are several different blockchain networks (e.g. Ethereum, Solana) that each operate in different ways, but stablecoin providers can operate on top of multiple networks.

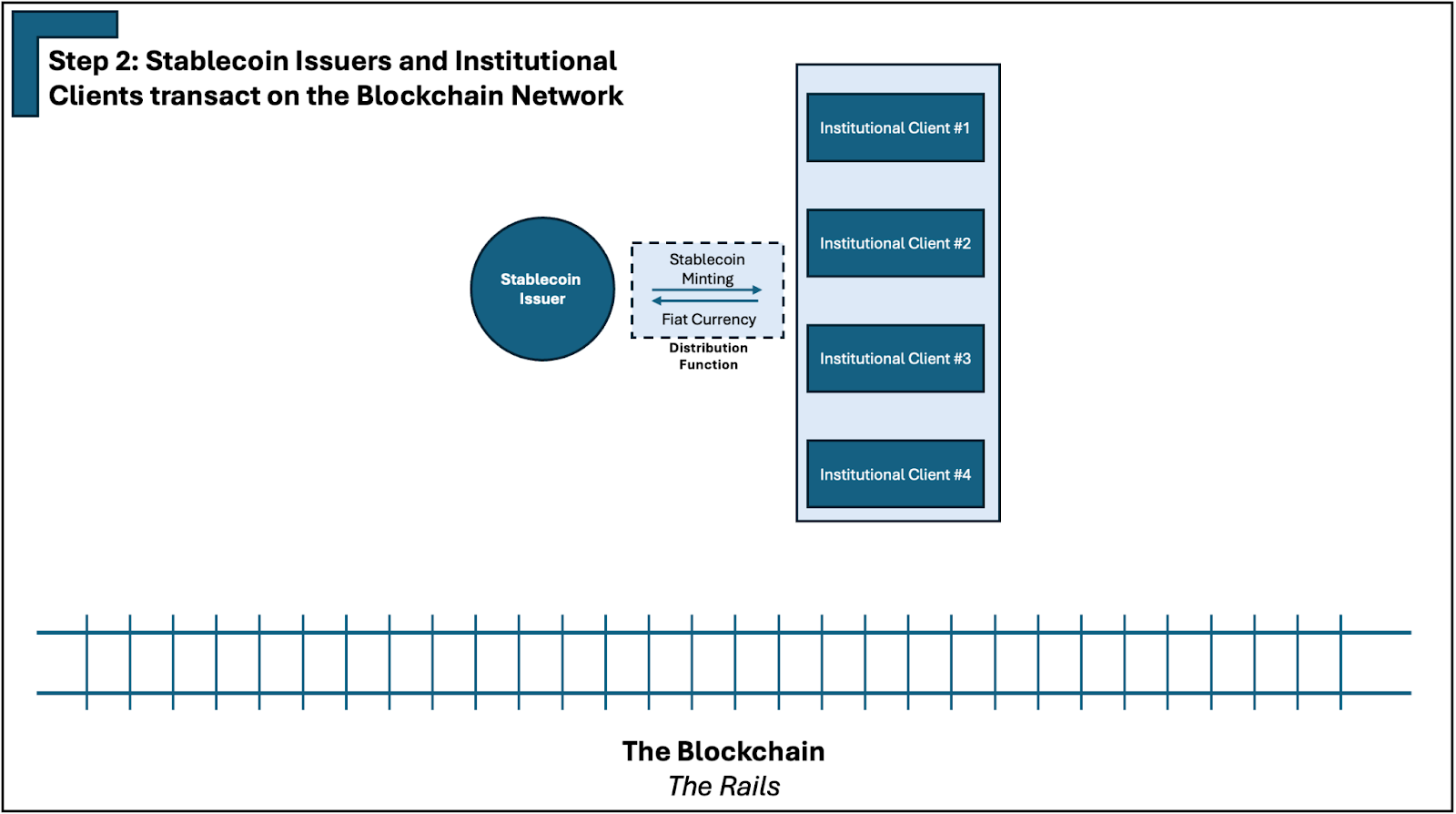

Stablecoin issuers like Circle, Tether and PayPal distribute tokens to a select group of institutional clients. These institutions send fiat, receive stablecoins, and are often the only parties that have direct access to redeem tokens at face value with the stablecoin issuer. These institutional clients often have to undergo rigorous AML/KYC checks and must meet minimum transaction requirements. This relationship forms the primary market for stablecoin transactions; this is where the 1:1 redemption can actually be enforced. It is also crucial to note, however, that a risk faced by stablecoin issuers is their dependence on access to the banking system through deposit accounts; if access is terminated, the issuer will be unable to redeem at par value (or any value, for that matter) as they cannot transfer funds into the redeemer’s bank account.

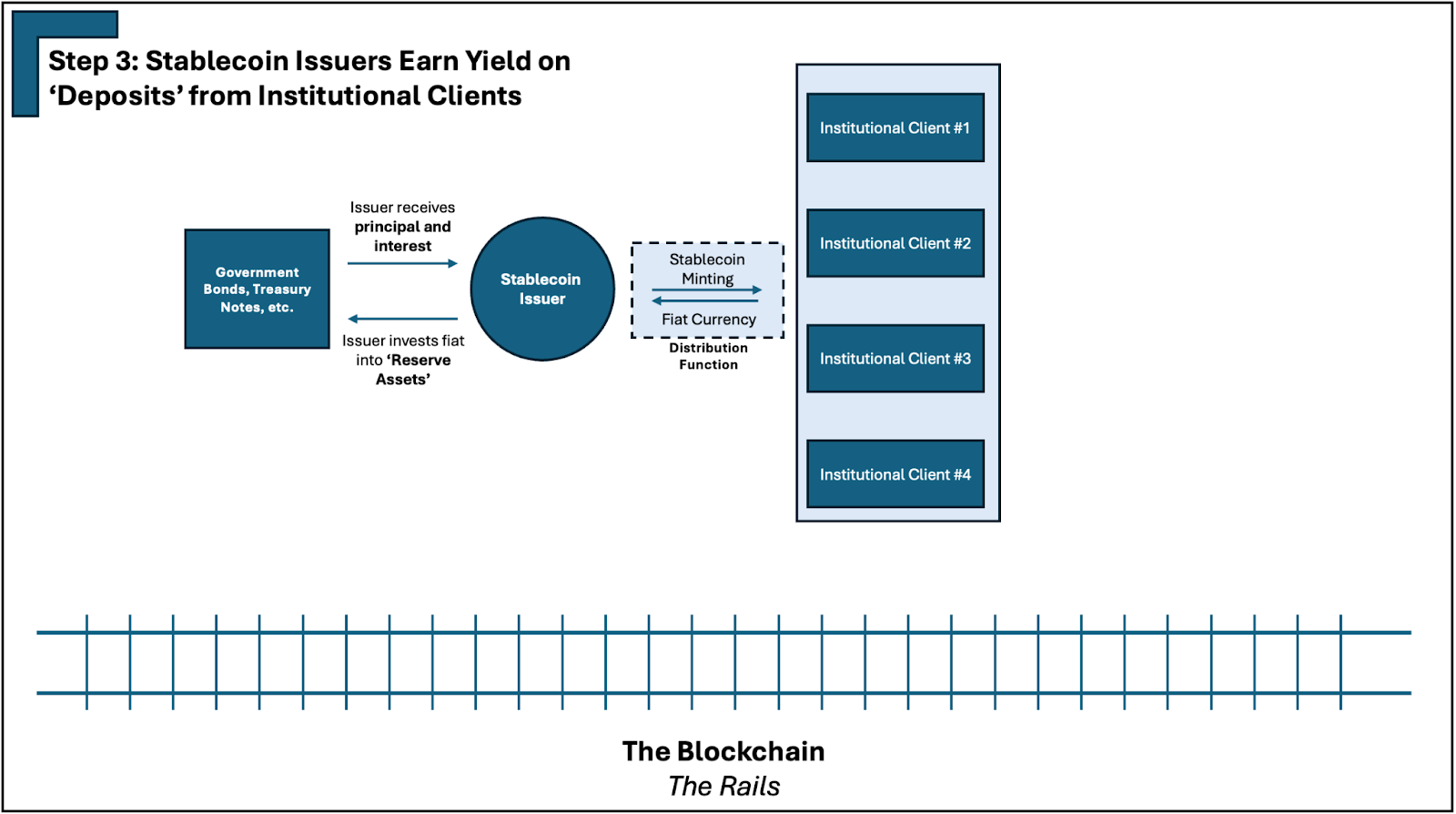

Stablecoin issuers then use the funds from institutional clients to purchase “reserve assets” that are ideally high quality and low risk, to earn yield while backing the minted stablecoins. Some stablecoin issuers custody their reserves with financial institutions (i.e., Circle’s reserve assets are custodied at the Bank of NY Mellon, and the assets are managed by BlackRock.) This reserve supports the redemption promise, but only if the stablecoin issuer is able to quickly and adequately sell reserves during periods of market stress.

Finally, users who do not have accounts with the stablecoin issuer must buy stablecoins on exchanges, either centralized (e.g., Coinbase) or decentralized (e.g., Uniswap). This forms the secondary market, where prices are driven by supply and demand, and not redemption mechanics. Simply put, if there is high sell pressure on stablecoins, the par-value exchange in the secondary market will be less than 1.

Managing the Peg

Fundamentally, the issue is not just about who can redeem, but instead about whether the issuer can actually meet redemption demand when it matters. While both institutional and retail users in the stablecoin ecosystem expect their tokens will be redeemable at par, this belief depends entirely on the issuer’s ability to convert reserve assets into fiat at par value. Confidence in the peg drops when redemptions are delayed, when reserves are inaccessible or when panic selling outweighs available stablecoin issuer liquidity. If stablecoin issuers are unable to meet the redemption demand, for whatever reason, then the peg can break.

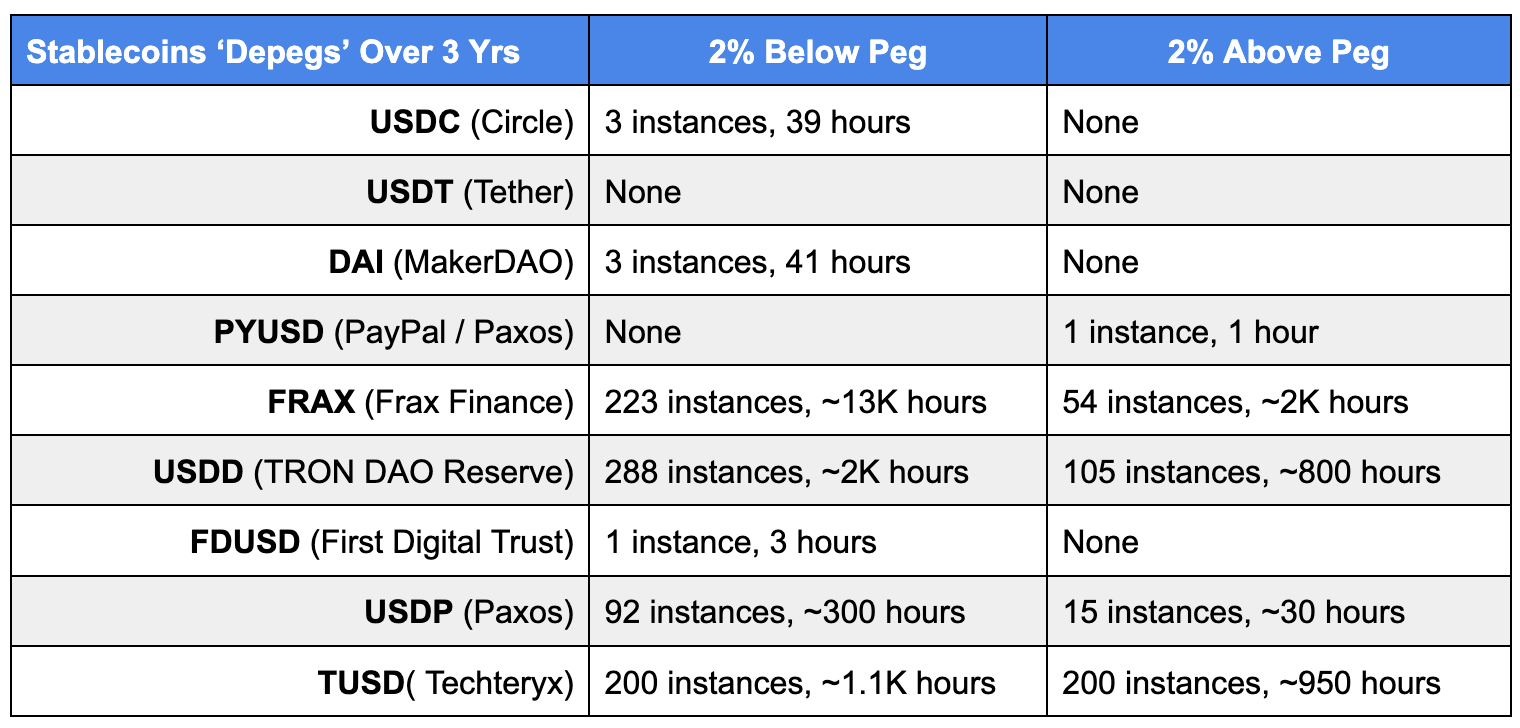

While there is no universally accepted standard for what constitutes a stablecoin depeg event, one common approach is to set a threshold for how far a stablecoin’s price can deviate from its fiat currency peg. Below we utilize data from the Cambridge Digital Money Dashboard to illustrate number of times the following tokens have broken a 2% fluctuation threshold:

When Silicon Valley Bank collapsed in 2023, one notable stablecoin issuer, Circle, which is responsible for the stablecoin USDC, tweeted that ~8% of their reserves were stuck at SVB. The secondary market reaction was swift; USDC dropped to $0.87. This elongated depeg only stabilized after the US government stepped in with a plan to make SVB depositors whole and investors resumed buying USDC (notably, at a significant premium!).

To make this clearer, let’s assume that Circle started with $40B in reserve assets and $40B worth of USDC in the market.

Circle tweeted that $3.3B of its $40B reserves were stuck at SVB; the secondary market got spooked

The market then adjusted and weighted the risk that Circle might be undercapitalized, which resulted in one USDC liability being worth as low as 87 cents on exchanges

Note that $36.7B reserve assets and $40B in minted stablecoins implied that each token should be worth $0.9175 (still, higher than the $0.87!)

On-chain data suggests that Circle processed at least $2B of USDC redemptions during this crisis, via a process called ‘burning’. This suggests that the primary market peg presumably held for institutional clients, even as the secondary market peg for retail users broke. The divergence highlights the structural gap between the redemption rights for institutional accounts and retail users.

The par-value redemption promise that stablecoins rest on is one that is partially true; secondary market depegs can happen, and can be exacerbated by panicked market participants. It’s important that those working with and regulating stablecoins understand this potential risk.

In our next post, we will explore whether stablecoins can be compared to existing instruments and whether it makes sense to borrow existing regulation from these comparisons.

Authors: Ashwanth Samuel, Dan Aronoff, Neha Narula

This post is part of a summer blog series from the MIT Digital Currency Initiative exploring the financial and technical risks of stablecoins. Read:

1:1 Redemptions for Some, Not All

Stablecoins and the Limits of Existing Analogies

Will Stablecoins Impact the US Treasury Market?

The GENIUS Act is Now Law. What’s Missing?

These posts preview findings from a forthcoming research paper, written in collaboration with MITRE, that will be released later this year. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of MIT or any other affiliated institution.