Will Stablecoins Impact the US Treasury Market?

Are stablecoins creating a new macroprudential risk because of their concentration in US Treasuries?

Stablecoin issuers hold a significant amount of US Treasury securities, which is a conventionally conservative strategy. But even the Treasuries markets can be susceptible to strain, and if stablecoins grow large enough, a run could cause these markets to seize. Regulators and policymakers will have to face the question of whether stablecoin issuers should have access to the Fed Discount Window, and if not, what, if any, structural safeguards are needed to protect the US Treasury market?

Stablecoin issuer portfolios often contain a large majority of US Treasury securities (including repos). Although stablecoin issuers may also hold other assets - including cash, gold, or even Bitcoin - US Treasuries and Treasury repos make up a significant share of their reserves. Like money market mutual funds (MMMFs), stablecoin issuers purchase Treasury securities because they are widely regarded as the safest and most liquid security in the world. And separately, some believe that stablecoin issuer demand for US Treasuries can reinforce US dollar supremacy, further encouraging issuers to hold more Treasuries (a view also shared by US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent).

But just because stablecoin issuers hold ‘safe’ assets does not necessarily mean that the system itself is safe. In fact, stablecoins may be introducing new forms of liquidity risks into the very Treasury markets they rely on for credibility.

While it is tempting to assume that stablecoins are secure because they’re backed by US Treasury securities, the more crucial questions are:

Are stablecoin owners protected by the fact that stablecoin issuers hold so many treasuries, or might there still be remaining risks, even with these safe assets?

And as stablecoin issuance grows, could the potential of a stablecoin run cause a disruption in the US Treasuries secondary and repo markets?

In this post, we take a closer look at whether stablecoins could (or already have) introduced fragility into the US Treasury market that underpins much of their current value.

A Stablecoin Issuer’s Strategy

US Treasury securities are debt obligations issued by the US government to finance government spending. When someone buys a Treasury security, they’re effectively lending money to the government in exchange for a promise of repayment, with interest. Overnight Treasury repurchase agreements (or overnight repos) are short-term loans where one party sells US Treasuries to another with a promise to buy them back the next day at a slightly higher price. For stablecoin issuers, this provides near-instant liquidity while minimizing price risk.

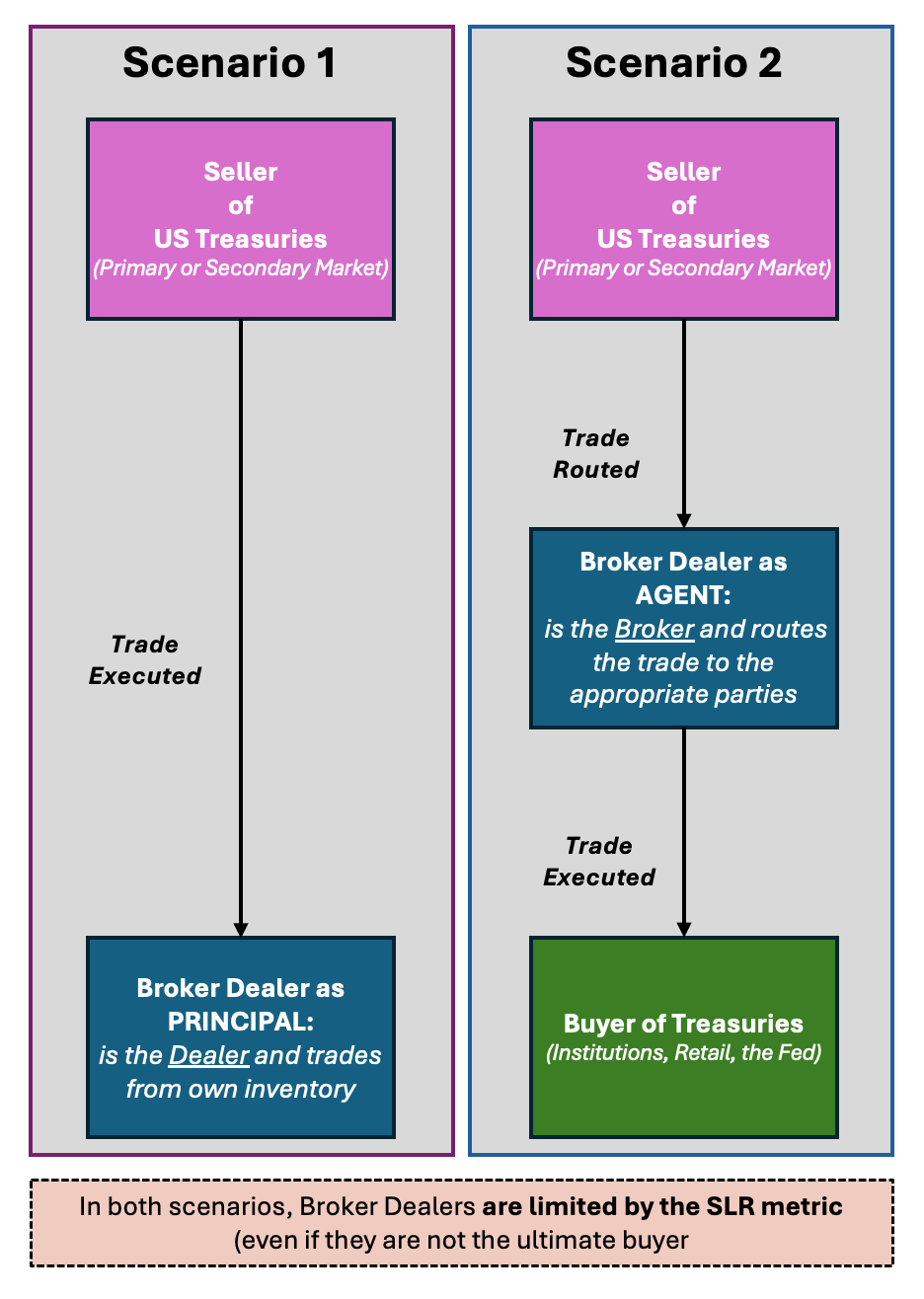

Figure 1: Broker-dealer roles in purchasing and intermediating US Treasury security trades

Importantly, the secondary and repo markets for treasuries are intermediated by broker-dealers, financial institutions that can buy and sell securities (see Figure 1).

For example, Circle purchases Treasuries today from a broker-dealer subsidiary of a bank who repurchases tomorrow at a fixed price. This provides three additional layers of safety for Circle:

(i) the broker-dealer counterparty guarantees to repurchase

(ii) the broker-dealer provides excess Treasuries collateral which Circle can sell if the counterparty defaults and

(iii) the daily exit from, and entry into, new repos enables Circle to reduce the possibility of capital loss, since Circle can liquidate its treasury holdings on any day by electing not to enter into a new repo.

Finally, the Fed’s standing repo facility makes it the “dealer of last resort” in Treasuries markets by providing a facility for broker-dealers to swap bank deposits for Treasuries at a targeted rate in effectively unlimited quantities. All of this adds up to the conclusion that investing in overnight Treasuries repos is the safest and most liquid allocation of assets that a stablecoin issuer can attain.

The Safest Investment May not Be Risk-Free

Just because Treasuries are considered “safe”, however, does not mean they are entirely risk-free. There are two main types of systemic risks in any securities market:

Collateral Fragility refers to the risk that even generally safe and high quality assets, like US Treasuries, can lose liquidity or experience sharp price drops during times of market stress. Ironically, this is when safe assets are needed the most by users (because users expect to be able to redeem their safest assets). The key issue is whether the market can absorb large-scale selling of Treasuries without dislocating prices. If too many actors try to sell Treasuries at once, and there are not enough buyers, even safe assets can become dangerous.

Concentration Risk is centered around an entity being too exposed to a single type of asset. For instance, if a portfolio is heavily weighted towards a single equity, and that equity experiences a massive price drop, the entire portfolio’s performance will likely suffer. The underlying idea here is a lack of diversification, which leaves institutions vulnerable to correlated shocks across their holdings.

Figure 2: Highlighting the differences between collateral fragility and concentration risk

Because much has been written about the concentration risk of US Treasuries, this post focuses on a different question: could stablecoins themselves introduce fragility into the Treasury market? This is why we specifically examine the potential for collateral fragility, the risk that large-scale, synchronized redemptions by stablecoin issuers (potentially caused by a run on stablecoins) could overwhelm the Treasury market liquidity.

Intermediary Balance-Sheet Constraints: SLR and VAR

A broker-dealer’s total transaction volume is rate-limited by two things, regardless of the size of supply or demand at either end:

Their balance-sheet capacity (constrained by metrics such as SLR and VAR)

Their willingness to intermediate

Supplementary Leverage Ratio

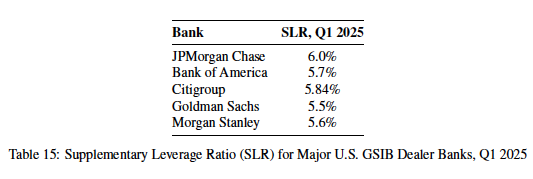

The Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) dictates that large banks (Primary Dealer Banks) must maintain at least 5% of Tier 1 capital against their total leverage exposure, which includes Treasury Securities. In recent years almost all of the Primary Dealers have operated near their SLR limit, which leaves little room to absorb additional Treasuries on their balance-sheet, whether outright purchases or intermediation.

Figure 3: Primary dealer banks operate very close to the 5% SLR threshold (gathered by authors from public disclosures)

This is believed to have caused several disruptions to the Treasuries markets in recent years and has prompted concern that the risk of disruption will increase as net Treasury issuance increases in the future. The SEC’s central clearing mandate is a response to try and lower intermediary balance-sheet impact by netting trades. The Fed is now engaged in a review of the SLR limit and may eventually loosen that constraint.

In practice, that means even “safe” assets like Treasuries count against a bank’s balance sheet, because technically the bank is holding debt (even if it is US government debt). If a dealer bank is already near its SLR threshold, it may no longer be capable of purchasing US Treasury securities during a fire sale and thus, are no longer a viable buyer of Treasuries and cannot intermediate trades, even when there are willing buyers to absorb additional treasuries: in effect, the pipeline connecting the seller to the buyer is clogged.This could mean trouble for stablecoin issuers: if no institutional buyers step in to absorb the Treasuries stablecoin issuers need to sell, Treasury prices could drop simply because the regulatory requirements will not allow anyone to buy the asset.

Value-at-Risk

Value-at-Risk is a metric used by broker-dealers to measure portfolio risk.

Economists Adrian (IMF) and Shin (BIS) documented that broker-dealers rapidly adjust balance-sheets to changes in VAR, independently of regulatory requirements. The result is that during moments of stress, liquidity dries up when it is needed the most.

This poses a particular risk to stablecoin issuers. If market volatility triggers a “flight to safety” among owners of stablecoins, users may rush to redeem stablecoins to obtain FDIC-guaranteed bank deposits. To meet those redemptions, issuers may be forced to sell Treasuries into a market where dealers are stepping back, amplifying the stress and overwhelming the Treasury market’s capacity to absorb it (i.e., no one will be left to buy Treasuries.)

The Missing Element: Access to the Fed

The asset portfolio of a bank, which has 50-60% in loans on average - is far riskier than a portfolio of Treasuries. Nevertheless, a bank is less exposed to stressed financial markets compared to a stablecoin issuer, because a bank can access the Fed discount window to exchange its Treasuries for money. Notably, swapping Treasuries for dollars does not alter the bank balance-sheet, so it doesn’t affect SLR or VAR.

The key point is this: Stablecoins are a form of money, but they are not fully connected to the Fed-centered monetary system. They cannot hold Fed Reserves or borrow at the Fed discount window. By holding Treasuries, stablecoin issuers indirectly connect to markets where the Fed is the dealer of last resort, but they can only access the Fed indirectly though broker-dealer intermediaries. The liquidity of their Treasuries holdings is limited by the capacity or desire of broker-dealers to intermediate or absorb their Treasuries and stablecoin issuers are not assured liquidity because they cannot access the Fed as the lender of last resort.

March 2020 “Dash for Cash”

One of the most dramatic breakdowns in the Treasury market occurred in March 2020, when the price of the benchmark 10-year Treasuries plummeted by 5-6% over two days (a shockingly large price drop for US Treasuries, which are the most stable-priced securities in the world).

The meltdown was triggered by a wave of selling. Estimates of the uptick in sales range from $400-700B in Treasuries. Broker-dealers, limited by their SLRs, were unable to absorb the excess supply.

And while that is a large volume in absolute terms, it is less than 2% of the market capitalization of Treasuries. Moreover, if stablecoins reach the heights of, say, $1T, it is not inconceivable that a stablecoin run to redeem, by itself, could disrupt the Treasuries markets.

Typically, Treasuries are in high demand during crises, but in this situation, everyone was selling everything, including Treasuries! Facing an impending meltdown, the Federal Reserve stepped in with emergency measures and launched massive Treasury purchases to absorb the selloff and actually temporarily allowed the exclusion of Treasuries from the SLR calculation so that dealer banks could continue to participate in purchasing Treasuries. Without this aggressive response from the Fed, the Treasury market could have crashed.

Is This a Problem for the Treasury Markets?

Today, 99% of Circle’s and 75% of Tether’s assets are backed by US T-Bills ($130B directly) and repos ($45B)

Circle and Tether currently interact with ~2% of the total $6.0T US T-bill market and 0.4% of the total ~$12T repo market. Forecasts estimate that stablecoin demand for just US T-bills could reach $1T by 2028 – notably, this forecast excludes demand for US Treasury repos

There is roughly $700 - 900B of daily turnover in the entire US Treasury market (includes T-Notes and T-Bonds) and $4-5T daily turnover in the repo market (source)

It follows that if there is a complete run on Circle and Tether today, forcing them to attempt to sell all reserves :

The $130B in T-bills could represent ~20% of daily turnovers in the entire US Treasury market

And their $45B in Treasury repos could represent 1% of daily turnover in the repo market

Stablecoin issuers, compared to other major holders, account for a much smaller portion of the overall treasury market. For example, MMMFs hold over $2.9 Trillion in US Treasuries, around 10% of the total $28T treasury market. But, as we saw during March 2020, it is no longer inconceivable that redemptions occurring even across a modest proportion of the US Treasury markets could destabilize the entire US Treasury market.

Conclusion

Stablecoin issuers’ portfolios are short-duration, highly liquid government securities (safer than most commercial banks). And yet, because stablecoins are redeemable 24/7, operate with minimal oversight, and lack direct access to the Fed, they are structurally more fragile than commercial banks.

If redemptions spike during a period of market stress, stablecoin issuers may be forced to sell Treasuries into a market where intermediaries (broker-dealers) may not be available to absorb the flow.

As policymakers continue shaping the regulatory perimeter for stablecoins, which are growing at a rapid pace, a key question will emerge: will stablecoin issuers have access to the Fed discount window, and if not, what, if any, structural safeguards are needed to protect the US Treasury markets?

In our next and final post for our Stablecoin Summer Series, we’ll explore how the GENIUS Act begins (or fails to) answer that question and where gaps remain.

Authors: Ashwanth Samuel, Dan Aronoff, Neha Narula

This post is part of a summer blog series from the MIT Digital Currency Initiative exploring the financial and technical risks of stablecoins. Read:

1:1 Redemptions for Some, Not All

Stablecoins and the Limits of Existing Analogies

Will Stablecoins Impact the US Treasury Market?

The GENIUS Act is Now Law. What’s Missing?

These posts preview findings from a forthcoming research paper, written in collaboration with MITRE, that will be released later this year. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of MIT or any other affiliated institution.